~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

- European authorities are busy doing the equivalent of rearranging the deck chairs on the sinking Titanic.

- Europe cannot be saved by giving etiquette diagrams to migrants, by setting up women-only railway cars, by covering up police records and statistics on the extent and seriousness of migrant crime, and by making a show of appearing to take some control over migration.

- All those acts are meant to appease the ever more alarmed voters, who are now flocking to join anti-EU and anti-Islamization political parties.

- The establishment parties, mostly left or center left, are afraid to lose their grip on power, and have taken to cracking down hard on any public criticism of migrants and Islam, while they let migrant criminals run rampant.

- The truth is that EU authorities DO NOT WANT to stop this wave of Muslim migrants. Even if they stopped all migration today, Europe has already been irreparably damaged.

- One conclusion we can draw from this situation is that EU politicians are deeply complicit with the plan to destroy European civilization by replacing it with Islam - a culture that only produces war, oppression, backwardness, intolerance, injustice, ignorance, and gruesome violence.

The motherlode of DUMB DEALS has been reached between the EU and Turkey

The European Union sealed a controversial deal with Turkey on Friday intended to halt illegal migration flows to Europe in return for $3 billion in financial aid and political rewards for Ankara.

The European Union sealed a controversial deal with Turkey on Friday intended to halt illegal migration flows to Europe in return for $3 billion in financial aid and political rewards for Ankara.

But not only will it NOT halt the Muslim illegal migration flow, it will give 78 million Turkish Muslims visa-free entry into the EU as well as the fast-tracking of Turkey for membership in the EU.

READ MORE

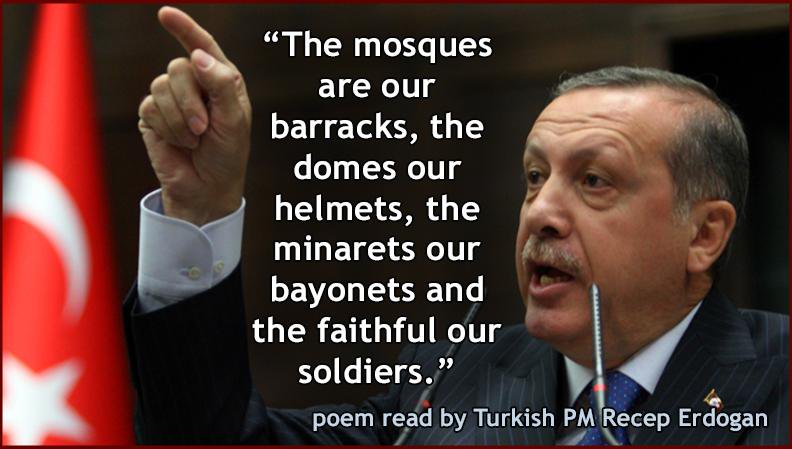

Erdogan - He wants Turkey to be a full member of the EU.

This is his, and all other Muslims' real agenda.

VIDEO - Nigel Farage on the absurd and dangerous deal with Turkey.

Nigel Paul Farage is a British politician and former commodity broker. He is the leader of the UK Independence Party, having held the position since November 2010, and previously from September 2006 to November 2009. Wikipedia

Nigel Paul Farage is a British politician and former commodity broker. He is the leader of the UK Independence Party, having held the position since November 2010, and previously from September 2006 to November 2009. Wikipedia

Please stay to the end of this video to listen to what Turks really think of Europeans, and what they want to do to them.

Continue reading, including a Daily Mail report on the migrant situation in Turkey and Greece, and see pictures of how the beautiful Greek island of Chios used to be before the migrant upheaval.

BREAKING NEWS:

BLACKMAIL: Erdogan Threatens To Sabotage EU Migrant Deal Unless Turkey Gets Visa-Free Travel

Turkey’s president has threatened to pull the plug on the European Union (EU) migrant deal should the EU fall short on any of his demands – including visa free travel for 70 million Turks by June.

On the 11th of January Mr. Erdoğan promised to “open the gates” to hundreds of thousands of migrants who could be transported into Europe by “bus” and even “plane” unless his demands were met in the lead up to the negotiations.

Later, during talk with the EU, Turkey made last minute demands for up to €20 billion in additional aid, even faster access to Schengen visas for Turkey’s 70 million citizens, and accelerated progress in its EU membership bid.

Deportations slowly began this week, with just over two hundred Pakistani economic migrants returned across the Aegean. However, any slip up or delay on the EU’s part could see the gates flung open once more.

“There are precise conditions. If the European Union does not take the necessary steps, then Turkey will not implement the agreement,” President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan warned in a speech at his 1,000 room presidential palace in Ankara.

However, Turkey still has 72 conditions of it’s own to meet before it can secure visa free travel, relating to such things as recognising Cyprus and press freedom. If the EU wavers in these, Turkey could be receiving “discounted” EU membership analysts warn.

“The worst reading of the EU-Turkey deal would be to imagine that Turkey is about to get a ‘discount’ on EU membership conditions just because of the refugees”, Marc Pierini, visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe, told AFP.

The increasingly autocratic Islamist President has been accused of “blackmailing” the EU over the migrants deal, as he has consistently employed such combative rhetoric.

Source

http://www.breitbart.com/london/2016/04/09/turkeys-erdogan-will-sabotage-eu-migrant-deal-without-visa-free-travel-in-two-months/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE EXPENSIVE, USELESS, AND DANGEROUS DEAL WITH TURKEY

You would think that after the very expensive deal with Turkey the tide of migrants has been stopped. It's only a pause.

Millions are determined to come into Europe using any route available. They know that the border situation in Europe is nothing less than chaotic, and they want to take advantage of that.

For every ineligible migrant returned to Turkey, Turkey will send a Syrian refugee into Europe.

On top of that, Turkey gets billions of Euros, and visa-free entry for Turkish citizens into Europe.

You might think the EU is finally getting to grips with the migrant crisis...but the human tide trying to get to Europe makes a mockery of the £4bn deal to send refugees back home

- The EU deal to repatriate migrants to Turkey gives £4billion to that country

- In return their authorities are meant to be deporting intercepted migrants

- First waves of migrants are being sent back through Turkey in the deal

- But nearly three times as many were landing by boat on Chios, Greece

As gaily painted fishing boats bobbed in the harbour on the Greek island of Chios, the forlorn group of migrants from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Morocco were once again at sea.

This time, however, all 64 were heading back the way they came — on a specially chartered red catamaran usually used by tourists — and each was accompanied by a police official.

They had been identified as economic chancers rather than genuine asylum seekers fleeing war, and on Monday were the first to be deported from Greece to Turkey under the EU’s flagship scheme to deal with Europe’s biggest humanitarian crisis since World War II.

On arrival in Turkey, they were bussed to a camp in the north, where their cases will be assessed and from where they ultimately face being returned to their homelands.

On neighbouring Lesbos, another key dropping-off point for economic migrants and refugees, a similar operation was under way, with 150 people shipped back to Turkey, which is the gateway to Europe for migrants from all over the world.

‘The operation went very smoothly,’ purred Ewa Moncure, a spokesman for Frontex, the European Union body responsible for policing our borders. ‘It was very calm. Migrants went on to buses with escorting officers and boarded the ferries. There were no incidents.’

The majority of these migrants are from Afghanistan, North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa

Yesterday, more migrants were deported from Lesbos, and even though there have been protests from migrants’ groups and human rights activists, you might be forgiven for thinking that the EU is finally getting to grips with the crisis.

Sadly, as I have discovered on Chios itself, and in Turkey, nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, the EU deal to repatriate migrants to Turkey — an arrangement under which that nation will receive a staggering £4 billion of EU taxpayers’ money, the right for all 77 million Turkish citizens to travel unchecked through Europe, as well as Turkey’s eventual EU membership — is doomed to fail.

This week, just as the first waves were being sent back from the island’s shores under the glare of the world’s media, nearly three times as many were landing clandestinely by boat on Chios.

Some 160 migrants arrived aboard rubber dinghies this week, eclipsing the paltry 64 people deported on Monday. On Wednesday, 39 made the passage and on Thursday, 58.

On one Chios beach where fishermen tend their nets, the shoreline is littered with discarded lifejackets and clothing.

The fishermen told me these illegal boat people were coming in droves. ‘You can see for yourself what the truth is,’ said one man. ‘We find their boats and lifejackets most mornings here. They dump their stuff here and then walk into town. Nothing will stop it.’

Later, on a winding track above one of the landing zones, I came across two new arrivals walking casually along the roadside.

The young men were brothers from Agadir. Far from being a warzone, Agadir is a beach resort in Morocco popular with tourists.

They had arrived overnight on a people-smugglers’ boat from Turkey, eight nautical miles away. They told me how, dreaming of a life of riches in Europe, they had flown from Morocco to Istanbul.

From there, they boarded a bus and travelled seven hours to Izmir, a town on the coast opposite Chios. A favourite with British tourists, Izmir is also the centre of the £4 billion smuggling industry.

Waiting in Little Raqqa for a boat to Chios, Greece.

The hub of the business is an area nicknamed Little Raqqa — a reference to the Syrian city where IS has made its base — an Arabic ghetto where Syrian and Turkish criminals control the lucrative trade.

Hundreds, probably close to a thousands, are waiting in Little Raqqa for boats to Chios. There, the two Moroccans made contact with one of these smuggling kingpins, who are reportedly helped by corrupt Turkish officials. Up to £50,000 can be made per boatload of migrants.

The brothers agreed to pay £500 each for a place aboard a boat to Chios. After handing their fee to the smugglers, they were taken by a bus driven by one of these criminals to a remote cove from where boats and dinghies leave nightly.

In Izmir, everybody knows where the boats leave from, suggesting Turkish officials simply turn a blind eye to a business that has seen at least one million people smuggled to Greece and then overland into Western Europe.

When I visited the area, it took me an afternoon to locate the main departure point — a small beach, hidden from the road by a hill.

Thinking I was an official, a group of refugees scampered up the cliff and ran off, looking at me over their shoulders. I spoke to others nearby and found many had lived in Turkey for years, making a nonsense of claims they were ‘fleeing’ war.

Back on Chios, I discovered the two Moroccans — Mustafa, 23, and his younger brother Medhi, 20 — had made the journey from the very beach I had visited in Turkey.

‘We were given lifejackets and put on a Zodiac [an inflatable boat],’ said Mustafa. ‘It took us less than three hours to cross.’

The brothers were told to get rid of their documents and pretend they were Syrians fleeing war.

I asked why they made the journey when Morocco is a safe country. ‘We have friends who travelled the same way and are now in England, France and Germany,’ Mustafa told me. ‘They say the governments pay you to live there and give you a house.’

We left these new arrivals at a camp at the port in Chios, where migrants had built tents and shelters from wooden poles and blankets, as bemused and angry locals looked on from cafes nearby.

Police had erected fences round this impromptu camp to stop people boarding tourist ferries to neighbouring islands. The official reception centre in a converted factory has been the scene of clashes between gangs of young males from Syria and Afghanistan.

Journalists have been barred from entering the complex after violence flared last weekend following the rape of a young Syrian woman.

But one senior Greek official was so angry with the terrifying daily chaos he has to deal with, that he asked to speak to me in private.

He produced figures for new arrivals to the camp since the deportations began, and told me that, for every migrant deported, at least three new arrivals were admitted after landing on beaches.

‘We sent 64 out by boat back to Turkey this week,’ he told me. ‘Since then, we have had 152 new people coming in.

'The week before, we had 300 new arrivals. The numbers don’t add up. This whole exercise is a lot of garbage.’

The latest official figures show 1,758 migrants — men, women and children — arrived in Greece between March 31 and April 6.

On Thursday, as the tourist season approached, the authorities gave the thousands of migrants and refugees camped out at Piraeus, Greece’s largest port, two weeks to move to army-built camps voluntarily or be expelled.

According to the Greek government, there are still more than 4,600 people in the makeshift camp.

That night in Chios, there were angry clashes as local Greeks confronted refugees living at the camp at the island’s port, throwing fireworks and bottles.

The same island official told me that fewer than 50 per cent of the migrants housed at his camp are from Syria or fleeing war. The majority are from countries such as Morocco, Tunisia, Afghanistan and from sub-Saharan Africa .

‘It’s all a big game,’ explained the official. ‘The prize is getting asylum in Europe. They think they will be given cars and houses and plenty of money. I feel sorry for the genuine ones with little children. But they are in the minority.’

Back at the unofficial camp by the harbour, where migrants had been holding up babies for the TV cameras and put up signs berating Europe for the deportations, I spoke to a number of people who were clearly trying to manipulate the system.

Somalis Abdi, 18, and Kani, 19, bought air tickets from their homeland to Istanbul. They, too, took a bus to Izmir before paying £400 each to travel by inflatable to Chios.

Both already had relatives who had made it to England: Abdi’s mother had left Somalia many years earlier and now lives in Wimbledon, while Kani’s uncle is in Birmingham.

Both had also previously flown from Somalia to Kenya and Uganda, where they had applied for asylum at the British embassies but been turned down. Their relatives could not support them — having been claiming benefits since arriving in UK — hence the refusal.

Now, after two years back in Somalia, they were trying again. They asked me for advice on how to convince EU officials in Greece that their cases are genuine.

‘Should we say we were threatened by Al-Shabaab [the terror group operating in East Africa]?’ asked Abdi. ‘What is the best story to tell?’ Yesterday, the unofficial camp where Abdi had put his questions to me was cleared by police overnight after clashes between refugees and locals erupted when one migrant tried to remove the Greek flag flying over the camp.

The migrants have been taken to centres elsewhere on the island, where they will await processing — and possible deportation.

The people of Chios — known as the Island of Tears on account of the drops of resin that are harvested from trees — were initially sympathetic to the migrants.

No longer. One elderly woman told me how she took food to migrants — only for it to be rejected for being ‘non-Arabic’, while she was harassed for wearing a Greek Orthodox cross around her neck.

‘I felt very sorry for them,’ she told me. ‘But I don’t any more. They are very angry and seem to think they are owed something by all of us here.’

Locals are furious about the mess and crime — and terrified by a catastrophic 85 per cent drop in tourist bookings.

So what is the answer? Many on Chios think that migrants who define themselves by their religion — Islam — should be resettled in Muslim states such as Qatar, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

But few migrants find this acceptable. ‘I want to go to Europe,’ said Mohammed, 19, who fled Syria a year ago and had been working in Turkey before coming to Chios this week. ‘I have friends there and I want to be with them.’

For those few being repatriated to Turkey this week, and for those who will be in the weeks to come, the chance of getting to their promised land has just become more difficult.

But my time in Turkey and on Chios suggests that will not stop them from trying — along with millions still determined to get to Europe and pay no heed to the EU’s £4 billion scheme to send them back.

Source

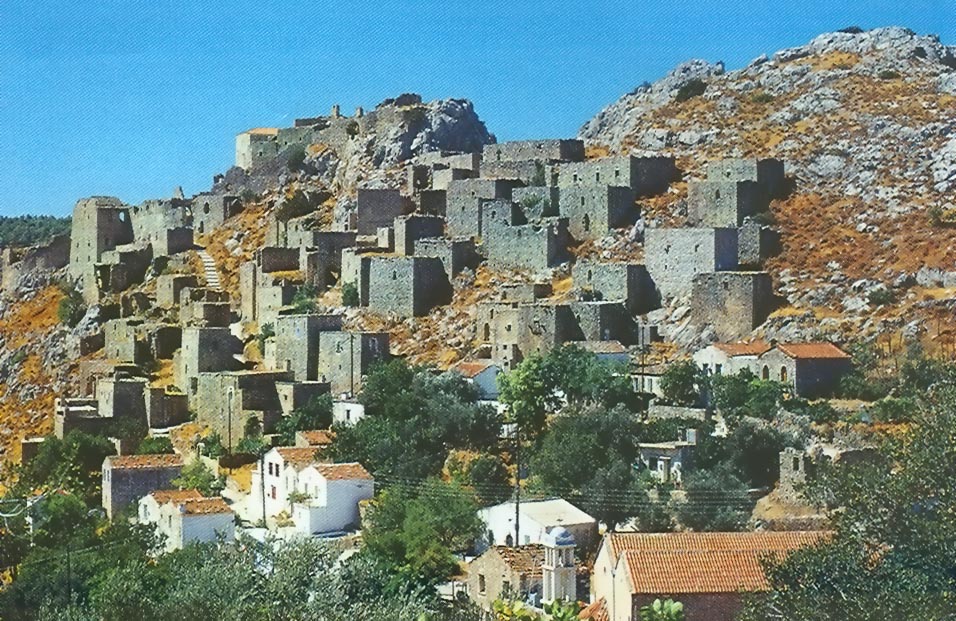

THE BEAUTIFUL ISLAND OF CHIOS

- IN BETTER TIMES

Europe almost got it right after World War II. Peace, tolerance, hard work, prosperity, safe cities, high tech, culture.

All that has now been trashed by Angela Merkel and her accomplices.

But that's not the worst of it.

The worst part is the utter passivity with which the majority of Europeans watch how their civilization is being destroyed and do absolutely NOTHING.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for visiting my blog. Your comments are always appreciated, but please do not include links.